|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. Welcome again to our monthly educational newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

Last month we looked at Favorites, a way of saving multiple Starry Night® preferences and options to show particular processes or events. This month we will look at Starry Night®’s SkyCal feature, which allows you to group a number of related favorites by their dates. If you open the SkyCal pane on the left side of your Starry Night® window, you will find a number of SkyCals displayed. These normally include SkyCals for the current month and recent months, plus a default SkyCal called ‘“Event Finder” Items.’ The latter contains whatever events are currently found using the settings in the Events pane, typically all events for the next month. One of my duties at Starry Night® is to produce the monthly SkyCal. This is downloaded automatically from the Starry Night® server by your copy of Starry Night® at the beginning of each month. I base each month’s SkyCal on events from a number of sources, especially the current Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, using data from their Sky Month By Month pages. I set up Starry Night® to display each event, and then save that event with its date in the monthly SkyCal. Since Starry Night® users are located all over the world, I set up these events as viewed from the center of the Earth. In order to see your local view, you need to change the location to your default location. Occasionally I will set the viewing location if the event is only visible from a certain location, typically for solar eclipses. The SkyCal is stored in a standard iCalendar format, a text file containing dates, times, and associated Starry Night® settings. This enables your copy of Starry Night® to reproduce exactly the settings that I used when displaying the event on my copy of Starry Night®. Thus a set of very complex Starry Night® images can be stored very compactly and efficiently in a small text file downloaded once a month. The SkyCal pane also lets you set up your own event files. For example, a few months ago I wrote an article about the top ten observing highlights of my astronomical life, and I illustrated this with a SkyCal file which anyone could download. Because these were specific events which I observed at specific locations, I could transport my readers to many different locations to show them exactly what I saw there, as reproduced by Starry Night®. Quite amazing to compress 52 years of astronomy into a 900 KB file! If you create a SkyCal file of your own that you want to share with your friends or colleagues, it’s important to know where Starry Night® stores them. Like many Starry Night® files, there are two possible locations. Files which are downloaded by Starry Night® automatically are stored in the Sky Data folder, available to all users on a given computer. Files which are created by the user are stored in their personal file storage area, inside a Starry Night® “Prefs” folder. The exact location varies depending on which version and platform of Starry Night® you are using. If you move a SkyCal file from the individual user area to the Sky Data folder, you will make it available to all users of Starry Night® on that computer. You can also attach it to an email and send it to other users. Geoff Gaherty

In recent issues, I’ve described the pros and cons of refractors, Maksutov-Cassegrains, and Schmidt-Cassegrains. This time I’ll talk about the fourth major telescope type, the Newtonian reflector. In some ways, I’ve been saving the best for last, since most of my favorite telescopes are Newtonians, and they’re the ones I recommend most often to beginners because they offer the greatest performance for the price of any telescope type. Since aperture is the most important attribute of any telescope, you’ve got to love a telescope design that gives you the largest possible aperture for your money. But reflectors aren’t just “light buckets.” They also offer really fine performance in highly demanding fields like planetary observing and imaging. In the bad old days, many reflectors were home-made behemoths with mirrors best used for shaving. The modern Newtonian is a very different beast. Highly accurate parabolic mirrors are now being mass produced, and these are often mounted in lightweight telescopes, which are portable to transport to dark observing sites. Traditionally, Newtonians have been mounted on so-called “German” equatorial mounts, or GEMs. These are “German” in the sense that the first such mounts were invented by German astronomer Joseph von Fraunhofer, though nowadays they are built in many different countries. The main advantage of a GEM is that it allows simple and accurate tracking of astronomical objects as they traverse the sky. Its polar axis is aligned parallel to the Earth’s axis of rotation, so that a simple motor can turn the telescope clockwise as the Earth turns counter clockwise. The result is that the telescope remains pointing at a fixed point in space. This is handy for visual observations and absolutely essential for astrophotography. The downside of GEMs is that they require heavy counterweights and are awkward and counter-intuitive to use.

Orion sells many different models of Newtonians in both mount designs. Since I’m primarily a visual observer, I lean heavily towards the Dobsonian designs. These range in size from 4.5 inches to 12 inches in aperture. My favorites are the 8-inch and 10-inch size, which to me represent the best balance between portability and power. Orion also offers GEM mounted Newtonians in apertures from 4.5 inches to 10 inches. Any equatorially mounted reflector larger than 10 inches is pretty much a permanent observatory telescope, and beyond the range of most amateur astronomers. I particularly like the Orion 8-inch reflector on the elegant and reliable Sirius mount.

Some of Orion’s equatorial mounts are available with the same IntelliScope feature, but several are also equipped as full “GoTo” telescopes. These also have locator computers, but are motorized so that the whole procedure becomes automated: the telescope finds the object and automatically tracks it. This comes at the cost of a bit of motor noise and a lot more battery consumption. For GoTo telescopes, an external power supply is recommended. So, which telescope is best? Newtonian, refractor, Schmidt-Cassegrain, or Maksutov-Cassegrain? It’s hard to say…each has its strengths and weaknesses. Different astronomers have different requirements; that’s why all four types are widely available and popular with many people. I generally recommend Newtonians because they offer the most aperture for a given price point, but I use and like each of the other types as well. That’s why I usually recommend that anyone in the market for a telescope attend a star party where they can actually try out each of the major telescope types for themselves, and make an informed decision as to which one is the best for them. Always remember that the best telescope for you is the one that you will use the most. Geoff Gaherty

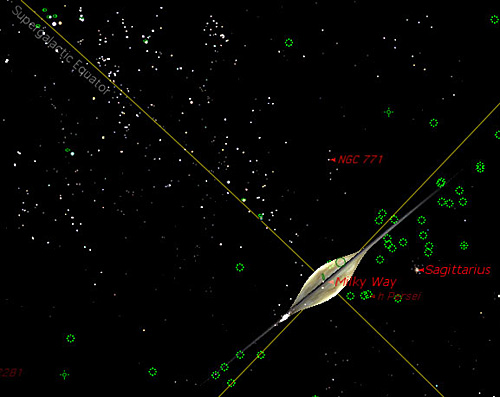

The Extragalactic Coordinate System Open up Starry Night® Pro or Pro Plus, and click on the Favorites tab. Browse to Deep Space -> Galaxies and click on Local Universe. The objects that appear as little white dots in the background are other galaxies. You might notice that the brighter ones tend to cluster around a line, which is actually a two-dimensional plane in space. (It looks like a line because our viewpoint is inside it – just like our own galaxy appears to be a band across the sky when viewed from the inside). Click the Options tab and open the Extragalactic Coordinates layer, and tick the box for Equator. You will see a line drawn through this distribution. This structure was first recognized in 1953 by astronomer Gerard de Vaucouleurs, who observed it when looking at the distribution of galaxies in the Shapley-Ames catalogue (a listing of over 1200 galaxies down to 13th magnitude). It was dubbed the supergalactic plane. The supergalactic coordinate system is based on this plane and centered on the Earth's position within the Milky Way galaxy. As with many other coordinate systems, supergalactic coordinates are specified by a latitude and longitude. If you're looking straight out into the plane, you're looking at 0º supergalactic latitude. The zero point of supergalactic longitude is the place where the Milky Way's plane intersects the supergalactic plane. This is a “right-handed” coordinate system – make a thumbs-up gesture with your right hand, and if your thumb is pointing in the direction of supergalactic north, your fingers will be curling in the direction of increasing supergalactic longitude.

Tick the boxes for Grid, Meridian, and Poles under Extragalactic Coordinates to see how the whole system fits together. If you hold down the Shift key and drag the mouse around from this view, you'll notice that the plane of our galaxy is almost aligned with the supergalactic meridian, but is not quite there. This system relies on our own place in space as little as possible. (If it looks like there is a strange absence of other galaxies along the meridian, that's because from Earth, the Milky Way itself blocks our view of anything along its own plane.) If you use the elevation button (marked with the carat or up-arrow ^ below the viewing location bar) to fly further out from our galaxy, the larger structure of the universe as we know it will come into view. The distribution of galaxies has less to do with the supergalactic plane the further out you go; it turns out that the supergalactic plane is not a universe-wide structure, but simply a smallish local grouping of galaxies and galaxy clusters near the Milky Way. Brenda Shaw

The Imperfect Moon In late July of 1609, Thomas Harriot of England made as simple drawing of the Moon using a spyglass. There was not much detail to be seen and Harriot did not publish his drawings. At this time, Galileo was still using his spyglasses for earthly endeavors but sometime during the fall of 1609 he turned his attention to the skies. By November, he had finished a spyglass that magnified twenty times and proceeded to make the Moon his first astronomical object of study. Between November 30 and December 18 of that year, he observed the Moon go through its phases and recorded his observations in a series of eight drawings He remarked that the dividing line between the light and dark part of the Moon was rough and irregular. It was obvious to him that the Moon was “...most evidently not at all of an even, smooth surface..” as had long been believed. Instead, he asserted that “..it was full of prominences and cavities..” similar to the mountains and valleys found on the surface of the Earth. The discovery surprised Galileo’s contemporaries, too. Most of them still believed Aristotle’s idea that the heavens were made of unearthly matter (“ether” or “quintessence”) that was immutable and incorruptible. The perfection of the heavens was a cornerstone of the beliefs of the day. The Moon should have been a smooth, perfect sphere. Suddenly it was shown to be something quite different.

Caption: Galileo's wash drawings of the Moon. In his famous work Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo published his drawings of the Moon and also speculated that it was a body similar to the Earth. Thus Galileo, not Harriot, is usually credited with the discovery of the lunar landscape. You can follow in Galileo’s footsteps and make your own observations. Simply load the file <Galileos_Moon.snf>. What was the phase of the Moon on November 30, 1609? What constellation was the Moon in on November 30, 1609? Hint: Press “k” on your keyboard to toggle the constellation stick figures. Challenge: Observe how the Moon changes appearance on subsequent days following Galileo’s initial observation. How does the phase of the Moon change over time? Herb Koller

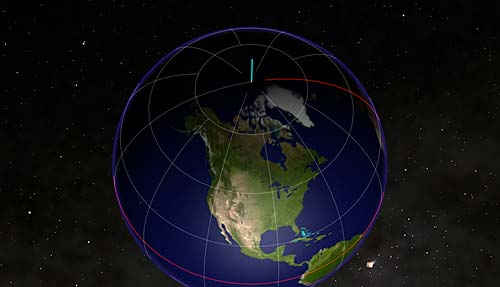

Start by opening the following file in Starry Night®: <NP_terminator_moving.snf>. Next, press the Run time forward button to watch the Earth revolve. This scene emphasizes how the Earth's terminator varies in covering the North Polar regions at different times of the year. The entire Arctic Region north of the Arctic Circle is totally illuminated on Jun. 21st, and completely darkened on Dec 21st. At the equinoxes the terminator slices directly through the poles. Observers at the poles on these dates would watch the Sun grazing the entire horizon during the day! Pedro Braganca

Leo is a large constellation, some 30° across, and well-placed for observation at this time of year, high above the southern horizon. The first of Hercules' fabled twelve tasks was to bring King Eurystheus the skin of a terrible lion whose hide was known to be invulnerable to spears and arrows. Hercules didn't have much bother with the lion: he cornered the beast in its lair and strangled it to death by ramming his fist down its throat. When he returned with the lion's body, the King was so terrified he ran from the sight of it. Hercules wasn't fazed: he skinned the lion and took its hide as armor. The Leo "Triplets" (M65, M66 and NGC 3628) are a nice grouping. The two Messier objects are brighter but the third triplet is visible too and, if you use averted vision, surprisingly large; it looks elongated and edge-on-ish. In the same field of view, the whole grouping looks like eyes and a mouth. M95, M96 and M105 are not so bright, but make an interesting group for comparison. Regulus, the brightest star in Leo and the 21st brightest star in the sky, has a faint double sometimes visible in binoculars. Algieba is one of the best doubles in the sky, with two yellow components that orbit one another every 620 years. Denebola, a blue-orange pair, is an optical double: the stars are far apart in space, not connected in any way, but lie along the same line of sight. Sean O'Dwyer

The Moon. Taken by William Russo with a Orion DEEP SPACE II COLOR CCD and a Canon EOS 40D. Using a Celestron CPC 11 telescope. Mesa, AZ.

RULES: We would like to invite all Starry Night® Education users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter. Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

May 2009

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a user of Starry Night® or as a registrant at starrynighteducation.com

To unsubscribe, click here.