|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

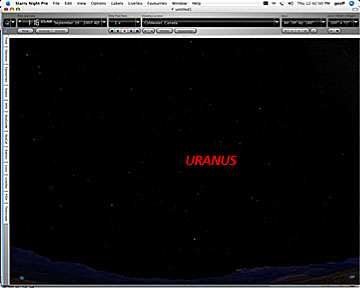

The reason why Uranus wasn’t discovered earlier was that, at its brightest, it is only magnitude 5.7, just on the borderline of visibility with the naked eye. This month gives us an opportunity to attempt the challenge of seeing this faint planet with the naked eye, as it reaches opposition on September 9, 2007. Even if you can’t manage to see it with your naked eye, it will be an easy target with binoculars or a small telescope. Here’s how to print a finder chart with Starry Night® to help you locate Uranus. Along the way you’ll learn some tricks to using Starry Night®: 1. Change the date either to September 9, 2007, the night of opposition, or to the night you plan to observe. You can change the date by clicking on each field and using the up and down cursor keys, or simply type in the number you wish to enter, using the numbers 1 to 12 for the months. Turn off Starry Night®’s clock by clicking on the central button under “Time Flow Rate.” 2. Find Uranus by opening the Find pane using the Find tab at the left side of the screen. Click in the check box alongside “Uranus” to get its label to display. Click on the menu button to the left of the word “Uranus” and choose “Centre.” If you get a message saying Uranus is not currently visible, click on the “Best Time” button. Otherwise, click on the Info tab and then click the “Transit:” button. Either way, this will place Uranus as high in the sky as possible. Your screen should now look something like this:

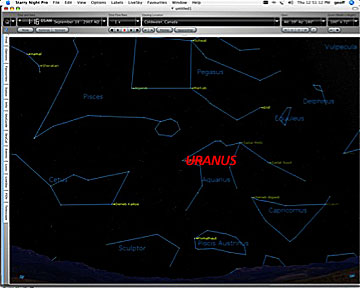

Well, we can see where Uranus is, but how do we find it? Let’s add some guideposts: 3. Turn on the constellation stick figures by going to the View menu and choosing Constellations:Astronomical. 4. Turn on the constellation labels by going to the Labels menu and choosing Constellations. 5. It would be nice to have some of the brighter stars labeled, so again go to the Labels menu, but this time choose Stars. Your screen should now look something like this:

Now we want to print out a chart which we can take outside to observe with. For this we’ll use Starry Night’s 3 pane chart feature, which automatically prints three charts on the same page: 6. Under the File menu, choose Print. You will see a print dialog box similar to this one. Carefully change all the settings to match what you see below:

I’ve set the first one to 90° for the naked eye view, the second to 10° for the view in binoculars, and the third (and largest) to 2° for the view in a telescope at low power. I’ve chosen “Use current settings” so that the labels and stick figures will display properly. I always turn on “Print legend” so that the date and time will be on the chart. Click “OK” and then “Print.” The resulting chart should look like this <uranus.pdf>. With this chart in hand, along with your red flashlight and binoculars, it becomes quite easy to find Uranus. The 90° chart shows you that it’s between the lower right corner of Pegasus (the star Markab) and Fomalhaut, the only first magnitude star in this part of the sky. Looking at that half-way point, you’ll see the stars Phi and Lambda Aquarius, and Uranus is very close to Phi. The 2° chart will let you zero in on Uranus with a telescope. Don’t expect to see much besides a tiny blue-green disk, as Uranus is very far from the Sun and very tiny. Seeing even the brightest of its retinue of moons takes a rather large telescope. For those of you who want to try, Starry Night® plots the positions of these moons accurately, telling you exactly where to look. This exact same technique can be used to plot finder charts for any object in the sky. You may want to add extra features such as the field of view of your binoculars, finder scope, or telescope eyepiece. This is just one of the many ways in which Starry Night® becomes a useful tool in the pursuit of the night sky’s secrets. Geoff Gaherty

There are two main kinds of telescope mounts, alt-azimuth and equatorial. Most books on astronomy recommend the equatorial mount, which is aligned with the Earth’s axis of rotation so that a simple motor on that axis will move the telescope in one direction while the Earth turns in the other direction, the end result being that the telescope's aim remains fixed in space, pointing at a distant object. This is essential for long-exposure imaging but it's also desirable for many kinds of visual observation.

The very popular Dobsonian telescope uses a simple version of the alt-azimuth mount. Its main disadvantage is that tracking an object across the sky always requires simultaneous motions in two different directions. With a badly designed mount, this can be a nightmare, but with careful design the observer no longer has to think about it, and tracking objects soon becomes second nature. Most of today’s Dobsonian mounts do this with ease, but alt-azimuth mounts for other telescope designs often don’t work as well. The commonest inexpensive alt-azimuth mount today is the AZ-3. This works very well for terrestrial viewing, but causes problems when used for astronomy. The mount is poorly balanced as it points higher in the sky, and the altitude tension is usually set very high to compensate. As a result, it’s very hard to point at anything high in the sky. Recently Orion® introduced an improved alt-azimuth mount, called the VersaGo. This consists of a standard tripod, similar to that used on many telescope mounts, and a newly designed head which attaches to the tripod. This head consists of four nicely-machined aluminum parts which bolt together with supplied hardware to make a very substantial and solid mount. Both axes have large Teflon bearings and clutch knobs, so the action of the mount is very smooth and well controlled. The upper plate, where the telescope attaches, uses a standard Vixen cradle as used on other Orion® mounts and those of other manufacturers, so that telescopes are easily interchangeable. The telescope dovetail is held securely in place by two large bolts. The altitude axis is offset, so that the telescope tube can be pointed at the zenith (not always possible in other designs). This also means that the telescope remains balanced no matter what altitude it points at. Finally, there is a long rubber tipped handle attached to the cradle which enables fine movements of the telescope.

Detail of the VersaGo head. Note the azimuth clutch, Orion® sells the VersaGo mount on its own, or paired with a variety of popular telescopes of different designs: 80mm f/5 refractor, 90mm f/10 refractor, 102mm f/13 Maksutov-Cassegrain, and 130mm f/5 Newtonian.

130mm f/5 Newtonian on VersaGo mount. Since I currently own none of these scopes, I tested the VersaGo with my Orion® 100mm ED refractor, which is comparable in many ways. Mounting was easy, thanks to the standard dove-tail system. I balanced the scope with my favorite 22mm Nagler eyepiece (41x, 2 degree true field of view). This made a perfect system for sweeping the grand vistas of the summer Milky Way, unencumbered by the complications of an equatorial mount. Although it’s easy to rebalance the scope for high power eyepieces by sliding the dove-tail fore and aft, I preferred to use a Tele Vue Equalizer: a solid bronze 2”-1.25” adapter which adds 12 ounces of weight to the eyepiece <https://www.televue.com/engine/page.asp?ID=167>. A quick twist of the altitude clutch holds the tube in place while changing eyepieces, an advantage over clutchless alt-azimuth mounts. The one problem I noticed was some vibration at high magnifications. I traced this to the tripod’s stamped aluminum legs. Aside from this, I found this to be an excellent product, clearly superior to Orion®’s older alt-azimuth mounts in every way. Even a scope as large as the 100 mm ED becomes a comfortable “grab and go” on this mount, easy to carry outside with one hand, and extremely smooth and solid in operation. Geoff Gaherty

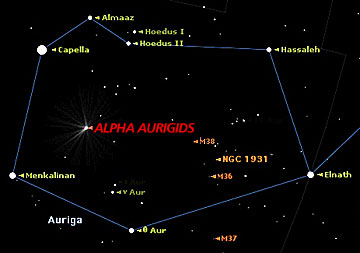

The Perseid meteor shower has come and gone, but that doesn't mean that there aren't any more good meteor displays to look forward to. In fact, another potentially good shower is just around the corner, scheduled to reach its peak during the early hours of Saturday, September 1st: the Aurigid meteors. The Aurigids get their name from the constellation of Auriga, the Charioteer. The meteors appear to emanate from a spot in the sky near the bright yellowish star Capella in Auriga. The Aurigids, however, are rarely mentioned in most astronomy guidebooks because, in any given year, they are hardly worth mentioning. Then why bother about a shower that almost nobody has heard of and that's due this year just days after a bright full moon? Because in 2007, these unheralded Aurigids are this summer's wild card.

Outburst in 2007? Aurigid outbursts are very infrequent, having been definitively seen on only three occasions: in 1935, 1986 and 1994. There were very few witnesses on each occasion, because these sudden outbursts were totally unexpected. But now, for the first time, an alert for an impending Aurigid outburst has been issued. At the 26th General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union Conference (held last August in Prague, Czech Republic) Jenniskens announced that the Aurigids would likely produce another round of unusual meteor activity on September 1 of this year. This forecast is based on calculations made by Jenniskens and colleague Jérémie Vaubaillon of Caltech, and on earlier work in collaboration with amateur astronomer Esko Lyytinen of Finland. The comet responsible for the Aurigids is well known: Comet Kiess, which last appeared in 1911. In carefully examining its movements, the meteor scientists have determined that prior to 1911, this comet previously swept passed the sun sometime around the year 82 BC (when Julius Caesar was alive). Jenniskens and Vaubaillon calculated that a trail of dust released by the comet at that 82 BC visit will run smack into Earth's path when our planet passes by on September 1. Far-western states favored On Saturday morning, September 1st, in the hour centered on about 11:37 UT, Earth should encounter the trail of dust released from Comet Kiess.

Hawaii (1:37 a.m.) and Alaska (2:37 a.m.) will also be in darkness when the Aurigids arrive, although Auriga will appear much closer to the northeast horizon. Like the previous outbursts, the upcoming display is expected to be short-lived: probably lasting no more than an hour or so at most. Unfortunately, most of the rest of North America will be out of luck: either bathed in bright twilight or daylight when the dust trail arrives. Jenniskens and Vaubaillon are forecasting a ZHR of 200. (The zenithal hourly rate is the number of meteors seen by a single observer under a clear, dark sky with the meteors' emanation point directly overhead.) Their outlook is very similar to Esko Lyytinen, who predicts a ZHR of 300, but with an added uncertainty of 1 to 3. Notes Lyytinen, "This would mean something between about 100 and 1,000. Let's hope this will be around 1,000!" There is, however, a significant drawback: a bright gibbous moon will be lighting up the sky on the morning of the shower. But because the Aurigids rip through our atmosphere at exceptionally high speeds of 41 miles per second (66 kps), and since these particles are predicted to be rather large, the display is expected to be rich in bright meteors, with many appearing as bright as the brightest stars and a few perhaps approaching or even rivaling Jupiter and Venus. "So," says Jenniskens, "the moon probably won't dim much of the display." Probably the safest bet is to play it conservative and forecast a rate of perhaps only 20 to 30 per hour, which is what was observed during the three previous Aurigid outbursts. But if those meteors are as bright as the calculations suggest they will be, it could still be a memorable, albeit brief, show. Joe Rao

From mid-northern latitudes Capricornus sails low over the southern horizon, between Sagittarius to its West and Aquarius to its East. Right off the bat, Neptune makes for an easy binocular target. Using a telescope, you can compare its subtle hue against Uranus' over in Aquarius. Dabih is an easy binocular double, hanging below Alpha Capricornus, an easy naked-eye double. The lower pair are separated by 20,000 lightyears but are actually part of the same gravitational system; a physical double. The alpha pair are an optical double, the brighter lying 109 lightyears from Earth and the dimmer lying a further 578 lightyears along the same line of sight. M75, while technically in Sagittarius, is a nice Mag 8 globular cluster. The horizontal bar of a cross asterism at 62 Sagittarii points the way. M30 (NGC 7099) is a large, dense globular cluster, roughly 26,000 light years distant. Sean O'Dwyer

Phillip Holmes took this image of NGC 6188 from his backyard in Rockhampton Australia using a STL-11000M camera on a NP101mm F/5.4 telescope mounted on a G11 mount.

PRIZES AND RULES: We would like to invite all Starry Night® users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter.

Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

SEPT. 2007

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download

or as a registrant at starrynight.com. To unsubscribe, click here.